For the first time in more than a decade, British dance music is dominating the airwaves. Rudimental, A*M*E, MNEK, Disclosure and Duke Dumont talk about their all-conquering 1990s-influenced sound

British dance music is in rude health right now. Hackney four-piece Rudimental, producer Duke Dumont and Surrey brothers Disclosure have all scored top-three hits in the past few months – and a host of other acts are bubbling under the surface.

Throwing together elements of house, UK garage and drum'n'bass, these artists deliberately hark back to the 1990s while also sounding like the perfect present-day culmination of past club trends.

Links and collaborations abound between the main players. For example, Duke Dumont's chart-topping Need U (100%) featured guest vocals from A*M*E, an old school friend of producer MNEK who helped co-write the track. MNEK is signed to Rudimental's first label, Black Butter, an imprint that has become a hub for the scene. Fellow Rudimental collaborators Sinead Harnett and Syron are signed to it as solo artists, as are several of the emergent acts responsible for some lower-key yet still high-quality dance crossover hits of the year: Lulu James, Gorgon City, Clean Bandit. Indeed, one of Black Butter's earliest releases,Racknruin's Soundclash, featured Jessie Ware – whose route to mainstream success came first via the PMR label, home to Disclosure.

In two weeks' time Rudimental and Disclosure take their dance-pop crossover to Glastonbury – suggesting that even bigger things are yet to come.

Rudimental

The four men who form Rudimental are testament to what can happen when a broad range of skills and influences are channelled towards a common goal. Originally a trio, DJ Locksmith and producers/songwriters Piers Aggett and Kesi Dryden grew up in Hackney, and cut their teeth on London pirate radio station Déjà Vu (which also provided an early home for Dizzee Rascal) before making their mark in the UK funky scene of 2008-09.

Their debut album Home ranges from smooth deep house to rambunctious, dramatic drum'n'bass, and is packed with an anything-goes maximalism that recalls the UK's last great mainstream dance act, Basement Jaxx.

"We feel we brought back a little musicality to electronic music," says Aggett. "It went a little wayward with the David Guetta stuff." Amir Amor, the collective's fourth member, who joined in 2011, continues: "We make music in a very organic way. We don't necessarily come from a bedroom/headphones/laptop background."

Rudimental frequent open-mic nights to find unknown vocalists to work with and stress that they want to make music that doesn't only work in a club context: their songs work as well on a wet Wednesday in the office as at a rave. "They make you want to drive fast, to scream and shout and put your hands up at a festival, to do the dreaded cleaning on a Sunday," laughs Dryden.

Rudimental's role in the British dance revival goes beyond their artistry, though. They own the Shoreditch studio Major Tom's, co-founded in 2009 by Amor and Nick Worthington, the former XL A&R and founder of 679 Records. Major Tom's was started with the intention of becoming a space for "young musicians to make music without limits or time constraints", as Amor puts it, and to enable Rudimental to develop their sound organically in a self-contained environment. Now, it also functions as a hub for the roster of the band's Black Butter label.

From the outside, it seems like one big family; DJ Locksmith agrees: "They don't just come in, record their vocal, that's that. The relationship continues."

It helps that collaborations tend to come about via musical connections rather than randomly picked session singers; Aggett reminisces about the hour he spent with Harnett bonding over their mutual love of Lauryn Hill before she had recorded a note with Rudimental.

"It's the antidote to dubstep," laughs Black Butter co-founder and Rudimental's manager Henry Village of the scene that has sprung up around this cottage industry. "People's taste seems really broad right now. You're hearing garage, house, drum'n'bass, pop, reggae and dub, but it all feels like it makes sense."

Village attributes much of this to cultural shifts at a very traditional gatekeeper: radio. "1Xtra starting up [in 2002] really made a difference – it had a huge role in getting underground music to the charts," he explains. "It feels like a really exciting movement going on." AM

Duke Dumont

"If anything, I'll always be the answer to a pub quiz question," says 30-year-old Adam Dyment, aka Duke Dumont. He's talking about Need U (100%) – not just a surprise No 1 hit five years deep into his career but also the song that stopped Ding-Dong! The Witch Is Dead reaching the top spot after Margaret Thatcher's death. Dyment attributes the ebullient house track's success to the wider culture growing up around his genre. From his debut 2007 single, a bootleg of the Miami freestyle classic When I Hear Music which led to its original singer, Debbie Deb, sending Dyment a complimentary email, to last year's underground club anthem The Giver, soulful vocals and electro-tinged house are hardly new territory for him. Yet the decision to structure Need U as a verse-chorus-verse pop song and to bring in A*M*E as a real singer rather than rooting through his collection for a vocal sample that fitted the beat were both deliberate.

"A year or two ago, even with the same song, it wouldn't have had that momentum," Dyment says. Like Rudimental and Henry Village, Dyment also praises the changing face of Radio 1. "Annie Mac's been pushing my music since day one – and she was the first to play Need U."

Dyment's experience has provided him with valuable perspective on how club crowds have changed over recent years. "It's a younger crowd, definitely – and there are many more women at the parties I've played lately, compared to the ones I used to play. I think a lot more people are going out on Fridays and Saturdays than a few years ago, and this is what they want to dance to." Now, thanks to his new status, Dyment finds himself oscillating between his old and new worlds. "The day before Need U got to No 1, I was DJing an underground party in Berlin with the purest techno acts around [DJ Koze, Ikonika and Isolée at Stattbad]," he grins. "Then I come back to do student union parties in the UK. It keeps you on your toes."

Dyment considers the community spirit between himself, Disclosure and Rudimental an asset. "With the EDM guys, there's huge competition. I did a tour of Australia and got a minibus to the festival with a lot of UK house acts and French electro acts – we all knew each other, and not once was there mention of record sales or how much we were getting paid or what times we were playing," Dyment says. "On the way back, we were in a bus full of guys under the EDM banner, and all they spoke about was why they weren't headlining, how much more money they should've got and so on." He sighs. "It's from a different place, a different part of the brain." AM

A*M*E

Amy Kabba – also known as A*M*E – is irrepressible, frighteningly confident and prone to peppering her conversation with sentences that make anyone past their teenage years feel incredibly old. "We bonded over our love of 1990s music," she says of her relationship with producer and old school friend MNEK. "We were both born in 1994, so it was really hard to find people our age who loved that really old-school 90s stuff." Does she actually remember it from the time? She shakes her head: "Oh, no. But it must have been the most incredible time for music. Things being so live and raw, people belting out harmonies, Janet Jackson's sick moves, hi-tops and hair and Reebok trainers…"

It makes sense that A*M*E's approach to dance has been informed by hearing it on the radio rather than as a clubber. In fact, this whole movement can be viewed as what happened when kids raised on a diet of 90s R&B, hip-hop and dance music grew up and put what they learned into their own music.

The success of Need U (100%) also took A*M*E by surprise. She had already made the BBC's Sound of 2013 longlist before having much to show in the way of material – a K-pop-leaning early single, Play The Game Boy, had failed to make the top 100 – and was still in the process of finding her voice and the style of pop she wanted to make. Duke Dumont's beat was not initially a priority. "It was done in half an hour," she remembers. "MNEK and I were both really busy. We were like … sigh, can we be bothered to do it? But I did want to do a full song. Lots of people would say you can't do that with a dance track, there'll be too much happening, so we kept it simple and didn't overthink."

The singer, whose parents left Sierra Leone when she was eight years old, enthuses about the current "massive UK pop movement", singling Katy B and Jessie Ware out for praise. "The Americans have always sort of beaten us at pop," she says. "But we're stepping up, saying we're here now." AM

MNEK

Eighteen-year–old producer and songwriter Uzoechi Osisioma Emenike (or MNEK) has an ear for progressive pop music. His CV already includes writing and producing for Little Mix, Misha B and Rudimental.

Born in Catford and the recipient of a publishing deal by the time he was 14, MNEK initially had to convince his mum and dad that dropping out to pursue music was a good idea. "I have traditional African parents," he says. "They were a bit like: 'Stay in school!'".

Eventually they relented, allowing MNEK to concentrate on a sound that reflects the chart music he grew up with. "I've always loved two-step, garage, female vocals and 90s R&B," he says. "I grew up obsessed with people like Janet Jackson, Timbaland and Rodney Jerkins. I'm definitely more of a throwback to melodies and harmonies … I'm an old soul, I suppose."

He is also optimistic about the shifting state of pop: "I think it is being more experimental. Before it was littered with trance pop, which was basically just talking about nightlife. We're moving away from that radio fodder. This is a new era. The pop chart now has music people can dance to but it also makes you feel something." KY

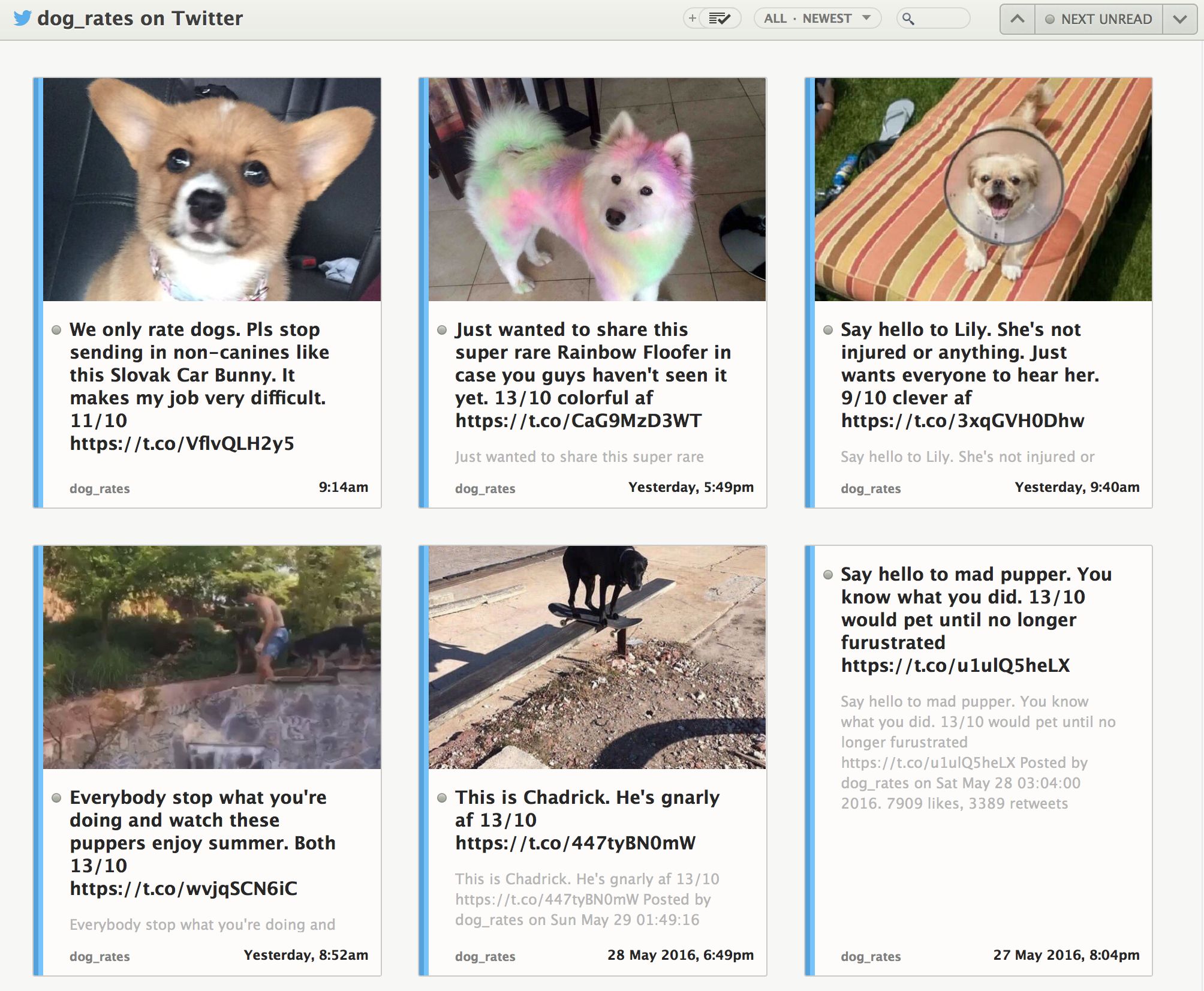

Disclosure

No act better encapsulate the changing fortunes of UK dance than Disclosure. A year ago, their UK garage-inspired productions were circulating on specialist radio, in clubs and online. Today, they are the most successful new dance act in the country, and as of this month have a No 1 album, Settle.

Settle is a masterclass in big dance production, classic beats from garage and house reworked into FM-friendly pop songs. Because of the commercial nature of their music, Disclosure aren't convinced that what's happening in the charts is a victory for dance music as we know it. "I think because people discovered us through underground tracks like Latch, they think we're long-time DJs who've just got into making songs," says Howard. "But we've got a much more varied background. I played drums in an indie band, one of Guy's favourite records is by Seal. We make pop music in the style of house."

Disclosure are keen not to put a name to the change that's been happening in the charts while still being supportive of those sharing in their success: "This year has had a run of brilliant No 1s: Duke Dumont, Daft Punk, Naughty Boy," they say. "If you had to pick between that and the last few years of pop music, well, the choice is obvious." SW